This is is part of the Pecha Kucha: A Special Families and Health Blog Series.

Family systems theory is the foundation upon which family-centered care is built. The following patient story illustrates two aspects of this theory. Although Erica is not her real name, her story is real, and she has given permission to share it to help demonstrate the value of family-centered integrated care.

Dan Felix, PhD, LMFT

Erica’s type 1 diabetes had been managed pretty well since she was diagnosed at age 6, but now at 19 she was being admitted to the hospital four or five times a month in diabetic ketoacidosis. Although Erica is not her real name, her story is real, and her story demonstrates the value of integrated care. More importantly, it demonstrates the value of family-centered integrated care.

Erica’s physicians—the family medicine residents who I teach—provided appropriate medical treatment each time she was hospitalized. They then sent her home only to see her back the following week with higher levels of blood sugar. “Why don’t you just take your medication?” was answered only by a gentle shrug of her hospital gown-covered shoulders. I was invited into the case with “Dr Felix, fix her. She’s not right in the head. She claims she doesn’t want to die but she sure is acting like it.” So I chatted with her at the bedside a couple of times, which was enough to convince her to come to see me in the clinic between her hospitalizations.

At first, we didn’t discuss her diabetes. Instead, I found out that she has been with her boyfriend for several months, which was a big deal to her. Relationships, I discovered, had never come easy for her, especially since childhood during which she endured abuses and betrayals.

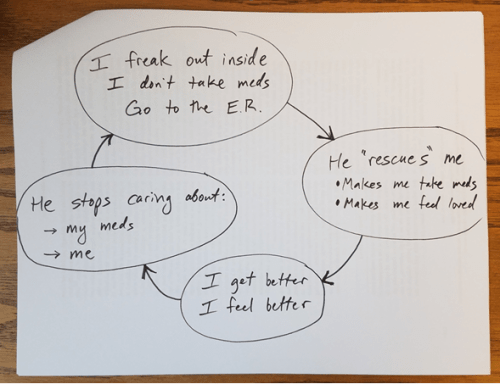

During the next appointment, with her boyfriend in the room, we explored what keeps them together and what pushes them apart. With amazing courage, she vulnerably declared her belief that she couldn’t stop being hospitalized because if she did he might leave her. We drew out their cycle. This is the actual paper we used:

Some people have been known to say things like, “I’ll kill myself if you break up with me” as an attempt to keep their relationship intact. She didn’t have to kill herself. Her uncontrolled diabetes was doing that for her. She simply needed to allow herself to be sick and he would rush in like Superman to save the day. He would manage her meds on her behalf to rescue her from this villainous disease that she appeared to have no control over. I remember when he first grasped what was going on. He turned to her and asked, “Is this true?” She sheepishly nodded that it was, to which he responded by abruptly leaving the room unable to look her in the eye. Thankfully he was willing to reenter, re-engage, forgive, and begin to work through it with her.

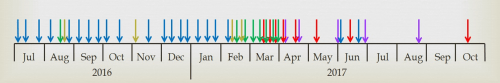

This cycle had been reiterating for many months. I went back through her medical records at both of the hospitals where my residents had treated her and mapped out a timeline of her hospitalizations.

Notice the drastic stop in blue and green lines (admissions to both hospitals). Why did they so drastically stop? Had we finally found the correct medication and dosage for her? The red lines are the family therapy appointments I had with her, and the purple ones are the outpatient follow-ups she had with our residents. She had traditionally no-showed most of her outpatient appointments because, I suppose, they weren’t medical crises where she was getting her emotional attachment needs met.